Bee Life Cycle – A Fascinating Journey of Life of These Fabulously Smart Creatures

Bees have been around for quite a while now, fascinating scientists and naturalists alike. These simple stinging insects have the most complex and well-organised colonies that could put a top-notch corporate firm to shame! And although we tend to often swat them away, bees can be a valuable help to any backyard gardener. Yes, contrary to popular belief, bees aren’t a menace but actually an indispensable part of the ecosystem. They aid in pollination and are hence necessary for maintaining the balance in nature. From the very start of their lives, bees lead an interesting journey, one that takes place in many stages and undergoes several transformations. Want to know more? We have discussed the life cycle of the common honey bee and other bees in a nutshell below:

Read here – How Long Do Bees Live

Honey Bee Life Cycle

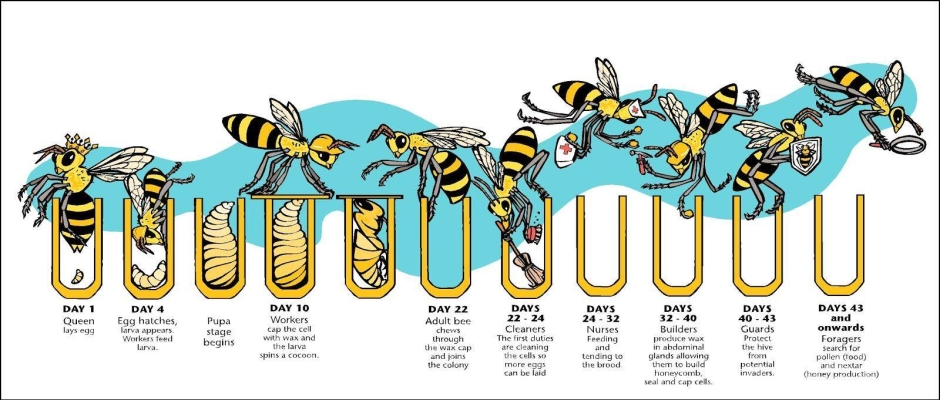

Before we begin to talk about the life cycle of the honeybee, let us first understand the terminology and the different classes of bees inside a colony. There’s the egg-laying queen bee, the sperm-producing drones and the working female bees that are infertile. The male drones die soon after mating with the queen, their phallus falls out and they perish. The worker bee lasts six weeks while the queen bees have a longer lifespan of five-six years at max. The life cycle of the honeybee are perennial, i.e. continues throughout the year. There are basically four distinct stages a bee has to go through – egg, larvae, pupa, and adult bee.

The life of a honey bee begins with the queen laying and hatching the eggs. During the first developmental stage, the digestive system, nervous system, and the outer covering are formed. Each member of the colony develops into an adult over varying durations. The queen takes 16 days, the drones develop in under 24 days and the worker bees require 21 days during the larvae and pupa development. A beekeeper must be familiar with the different identifications of the stages; the metamorphosis begins with the hatching of the egg. The eggs are pretty miniscule, about 1.7mm long. Finding the eggs are the surest ways to confirm that the queen is alive.

So, What Exactly Happens?

Now that you know about the different classes and their duties of a bee colony, you might want to know more about the various stages a bee goes through. We have discussed the different stages of the honeybee in detail below:

The Queen Bee Life Cycle

Queens live for over five years and are definitely the most important member of the colony. The worker bees raise a new queen bee once the old one dies. Once she has become an adult, she attends a nuptial flight and mates several drones. She is usually the largest of the colony and her sole responsibility is to lay eggs. She lay over 2000 eggs in a single day; however, she doesn’t fertilize them all at once. She stores the sperm and fertilizes the eggs over a period of time.

The Eggs

The worker bees (barren females) clean and prepare the cells for the queen to lay eggs; she hatches one egg in each cell. She positions the egg in an upright position at the bottom of the cell. Then she goes on to fertilize the egg, this develops into a worker bee. The drones are developed from non-fertilized eggs. It is the responsibility of the worker bees to balance the ratio of the female bees and drones. The smaller cells are for females, the males occupy the larger cells.

The Larvae

Three days after the queen hatches the egg, it develops into a larva. Healthy larvae can be identified by their snowy white color curling up at the corner of the cells. The larva takes a couple weeks to grow and shed their skin over five times. These tiny creatures have a pretty large appetite; they consume over 1300 meals a day! The nurse bees have the responsibility of feeding the larvae royal jelly and bee bread (a mixture of honey and pollen). The larvae grow swiftly, in just five days they grow tenfold in size. This is when the worker bees seal their cells with beeswax, the larva then spins a cocoon around them. The larva stays here until it develops into an adult.

The Pupa

The larvae once cocooned in their covering become pupae. Here’s where things begin to happen. Of course, these transformations are occurring beneath the wax capping. The little creature inside the cocoon begins to take the shape of an adult bee. The eyes, legs, and wings start taking shape, then the coloration of the eyes begin. It first turns pink, then purple, and finally becomes black. Finally, their bodies are covered with fine body hair. The entire process takes about 12 days after which the fully formed adult bee chews her way through her cocoon to join the colony.

There are significant variations between the different bee species, even the roles, and duties of each member of the colony change accordingly. Let us look at the lifecycle of the different type of bees:

Bumble Life Cycle

Bumblebees have a yearly life cycle, except for the tropical ones that survive for more than a year due to the availability of flowers. The queen bee is the largest, slowest member of the colony who is responsible for hatching eggs. She hibernates during the winters and then wakes up in summer super hungry; it emerges out of the soil and ventures out looking for food. Newly emerged queens feed on both nectar and pollen, thereby aiding in pollination. She then starts searching for a nest once her ovaries are full and she’s fertile. Each species has its own preferences – deserted nests, barren gardens, tussock grass patches – are all probable spots for nesting. If you find bumblebees flying around inside and around your property during spring, then they’re probably mating or nesting in your area.

The queen lays eggs in batches of 4-16 on a ball of pollen and then covers it with wax. The eggs are about 2.5mm long and appear like slightly curved pearly white sausages. She then broods over the eggs, the underside of their bellies are bare unlike the rest of their body for hatching the eggs. The eggs hatch in about 4 days, after which the queen goes out to feed herself and the larvae. The larvae grow to pupate and emerge as full grown adults.

Carpenter Bee Life Cycle

Carpenter bees, unlike the common honey bees, prefer to build their nests under the ground or on wood. The young bee emerges from the nests sometime around spring and has a 2-3 week time frame during which they have to find a mate, nest and also forage for food. Carpenter bees don’t live in colonies; they are solitary creatures that prefer to fend for themselves. A male and female bee nests and raises their younglings together. Carpenter bees live for approximately a year; the eggs are laid from late spring to early summer in nests drilled in wood or burrowed underground. The fully formed adult bees emerge out of the nests in late summer and repeat the whole cycle all over again. During winters, both male and female carpenter bees hibernate in the pre-existing nests and coexist with other bees and siblings. Come next spring, they again venture out to find new mates and expand the local population. The female bees live long enough to lay eggs and can last a summer; however, they usually perish in the colder months.

Carpenter bees start out their lifecycle as an egg. However, the mother has a lot of things to take care of before she lays these eggs and hatches them. For starters, she has to build a nest. Using her mandibles, the female bees drill minute half-inch holes into wooden objects, thereby creating a tunnel for laying her eggs. Once the eggs are hatched, a larva emerges, safe and sound inside the tunnel sealed in its separate cell. The pupa is the transitory phase where the larva metamorphoses into an adult bee in roughly seven weeks.

Leaf Cutter Bee Life Cycle

The leafcutter bees don’t comply with the generic diagram of a lifecycle of a bee. These bees are solitary nesters and have no worker caste, unlike honeybees. There are no worker bees or drones or queens here, every female can reproduce and raise her young ones. The females, however, prefer making their nests near other female leaf cutters. They help one another in nesting and raising their young ones together for better chances of preservation and longevity. The leafcutter bees belong to the Megachile family and are somewhat similar to the earth-digging mason bees we’ll talk about later. They usually nest in cavities or soft rooting wood that can be excavated. Once they have agreed upon a suitable spot the bees begin to build cells using leaves and twigs. The newly emerged females immediately begin constructing their nests in spring. They then venture out; find mates and lay their eggs in separate cells.

The cells are stocked with bee bread, nectar and pollen, providing enough nutrition to the larvae when it hatches. The larva is cocooned and sealed inside the cells where they develop and eventually pupate into adult bees. It takes an entire winter for the larvae to mature and develop into adults next spring or summer.

Mason Bee Life Cycle

Manson bees belong to the Megachilidae family and use mud for constructing their nests. They are solitary, non-aggressive and generally amiable creatures that work alongside honeybees in pollinating the flowers and maintaining the ecological balance.

Mason bees share certain nesting habits and behavioral characteristic with the leafcutter bees. For starters, both species have no colonies or distinction of duties and classes. Also, unlike honeybees, each female can raise her younglings and prefer nesting in hordes for better survival chances.

The adults emerge from their cocoons or sealed cells after a long winter of hibernation. The males appear first and wait for the females to come out and mate with them. The male bees are smaller with dark patches of hair on their faces; they swarm around the nests awaiting eagerly the arrival of female bees.

The male immediately dies after the mating while the female moves on to look for a suitable location to build the new nest. She then lays the eggs, the ones laid in the front turn out to be males while the ones at the back are females. Once she has constructed the nest and laid her eggs in each of the cells, she would provide the necessary nutrition for the larvae. Over winter the larvae pupate, develop and finally emerge out as an adult in spring only to repeat the whole cycle again.